The significance of the Kurdish question

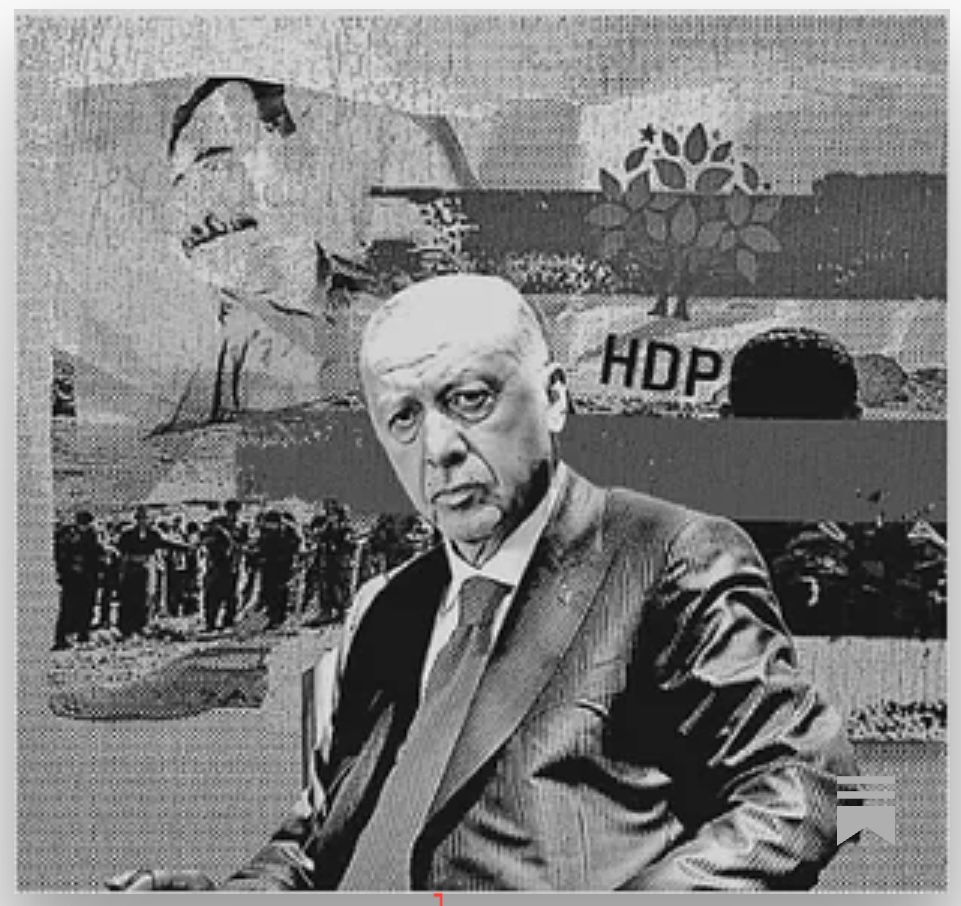

With good reason, 2025 in Turkey can be described as the year of the “Kurdish question.” The year now drawing to a close emerges as a pivotal moment for the Kurdish question in Turkey, as it has condensed the experiences of a long historical process of confrontation, negotiation, and incomplete transformations between the Turkish state and the Kurdish movement. Developments in this period cannot be understood in isolation from the strategic choices of the Erdoğan governing coalition, which seeks to redefine the terms of control, incorporation of the Kurds, and national security. Nor can the developments of 2025 be understood apart from the internal reconfigurations of the Kurdish movement itself – both political and armed – which is compelled to operate in an environment of heightened repression, institutional constraints, and almost world-shaking regional realignments.

From this perspective, 2025 has simultaneously marked a historic moment in which the demand for a political resolution of the Kurdish question returns to the forefront in an especially difficult period – one in which the possibility of dialogue coexists with the prospect of deepening conflict; the weakening of democratic channels of representation within Turkey; the intensification of authoritarianism under Erdoğan’s rule; and the escalation of military practices across the Middle East. This year, therefore, may be seen as a critical turning point in which the accumulated contradictions of the Turkish state – Kurdish movement relationship become not only visible, but also decisive for the next phase of the issue.

Given that the Kurdish question remains Turkey’s most decisive unresolved problem, the developments of the coming year – building on the legacy of 2025 – appear likely to determine, to a considerable extent, the broader orientations of the Turkish state.

Israeli aggressiveness and the process on the Kurdish question

When, at the end of 2024, the leader of the Turkish far right and Erdoğan’s governing partner, Devlet Bahçeli, called on Öcalan to speak from the National Assembly and proclaim the end of the PKK, almost everyone who engaged with the issue struggled to grasp the intentions behind this new policy. This was because the Turkish far right not only historically refused to accept the role of the imprisoned Kurdish leader, but additionally did not even accept the existence of the Kurds, and therefore the legitimacy of their claims. The situation became even more complex as, throughout 2025, it was indeed Bahçeli who assumed the main burden of publicly articulating the state’s policy on the Kurdish question in this new period. The new peace process that began – though it was never officially called such – ultimately led to the PKK’s decision to dissolve and disarm. On 24 November 2025, it reached a new high point with the meeting between the three representatives of the cross-party parliamentary committee and Öcalan in İmralı Prison.

What, then, was the driving force behind this process, which ultimately did not prove to be a mere communications trick? One serious – if not the most serious – reason for the initiation of a new process of talks on the Kurdish question, at least from Ankara’s side, was Israel’s aggressiveness and the profound realignments it has triggered in the Middle East. For Turkey, the period after 7 October 2023 marked an era of transformations and power vacuums with unpredictable implications for the country’s own future in the region. Developments suggest that military circles and intelligence services, as well as Turkey’s diplomatic apparatus, arrived at the comprehensive conclusion that the open wound of the Kurdish question must be closed. For the reproduction of the problem under conditions of dramatic transformation could turn it into a tool for other actors seeking Turkey’s total destabilization.

The basic positions of the parties in a future negotiation

After a year of developments in the Kurdish question, the main trends and dynamics shaping the positions of those involved are now clearer. The government and Erdoğan’s power bloc emphasize that the new process is focused on the goal of creating a “Turkey without terrorism.” This position, however, may also reproduce an authoritarian framework if it is not accompanied by an examination and removal of the causes that generated what the dominant ideological discourse in the country labels as terrorism. A “Turkey without terrorism”, that is, without the PKK insurgency, can be achieved to a certain degree even without a process of democratization. Yet this prospect cannot secure peace; it can only ensure an artificial, temporary, authoritarian – type stability of the political system under Erdoğan. The same direction may also be reinforced by the government’s tactic of “transfering” the Kurdish question as a regional issue into broader geopolitical balances and realignments. In this way, the Erdoğan government engages in a cynical calculation of advantages and disadvantages while avoiding issues of strategic importance for the country’s internal democratization – namely those issues that would definitively guarantee the political and cultural rights of Kurds within a democratic republican state.

The Kurdish movement in all its components – from the armed wing and the political party to its regional organizations – Is fully aware that under Erdoğan’s rule it cannot expect a thorough democratization of the country that would, as such, unequivocally secure all Kurdish rights. It can, however, aspire to an improvement in its position within the political system, to certain basic changes in repressive and anti-democratic laws, and to some protection of its gains in northern Syria. After all, it is there that the greatest disagreements with the Turkish state appear to exist, and it is there that Öcalan’s sharpest red lines are recorded.

At the same time, the Kurdish movement considers Öcalan himself to be the core of the process and insists that he must have a founding role. The party’s visits to the Kurdish leader, and above all the visit of the cross-party parliamentary delegation, show that the government too recognizes, at least to some extent, the central role and influence Öcalan should have. It also appears that he is being acknowledged as a leading actor in the negotiations. This is a historic achievement of the Kurdish movement itself. On the other hand, there is fear that Öcalan’s role will be confined solely to the level of disarmament, turning him into a counterpart of Turkey’s security forces rather than of the highest political level.

The gains of 2025 on the Kurdish question

So far, 2025 can also be recorded as a year of limited but substantive results in the peace process. On the one hand, under Öcalan’s guidance, the Kurdish movement proceeded to the decision to dissolve the PKK; to the withdrawal of guerrilla units from specific areas of Turkey and northern Iraq; and to the decision to disarm, symbolically marked by the burning of the weapons of 30 guerrillas. On the other hand, quietly, the Turkish state has improved Öcalan’s conditions of imprisonment; moved toward a relative liberalization of contacts between organized groups and him at İmralı prison; entrenched the pursuit of Kurdish political cadres and activists; and brought military operations to an end. In parallel, it consented to the creation of the parliamentary committee responsible for establishing a legal framework for resolving the internal dimensions of the Kurdish question. All of these can indeed be considered minimal steps within a twelve–month period of “slow” developments. Nevertheless, their significance lies in the fact that they are irreversible, and whatever process continues in 2026 will be compelled to build upon these gains.

The contradictions of peace process

A central problem of the current process is the absence of its societal engagement. The peace promoted by dominant political and state actors does not necessarily constitute the end of conflict; rather, it often functions as a strategic “pause,” within which the very “political economy of war” is restructured. In this context, the AKP government’s approach understands the process primarily as an instrument of stabilization and economic utilization of Turkey’s periphery, aiming to open new markets and expand the fields of action of Turkish capital, particularly across the wider Middle East.

This perception also explains the systematic absence of mass mobilization and meaningful social participation in the process. Peace is not presented as a collective social project, but as a technocratic and state-controlled management of a “security problem.” As a result, society remains a passive observer rather than an active subject of the process. Under these conditions, the need emerges to build an alternative peace “from below”, a peaceful order that will not be limited to the cessation of armed conflict, but will be grounded in democratic participation, social justice, and political recognition.

The different tactics of the opposition

The absence of meaningful social participation is, among other things, directly linked to the internal contradictions and differing strategies of the opposition. The Republican People’s Party (CHP), as the main force of parliamentary opposition, pursues a policy of immediate, day-to-day reactions to state repression and to the government’s prosecutions. This tactic, although necessary for the party’s political survival, traps the CHP in a logic of constant defense, limiting its capacity to formulate a long-term strategy of intervention on the Kurdish question. By contrast, the DEM Parti adopts a more long–term strategy of “patience” and political steadiness. It seeks to keep the process of resolving the Kurdish question alive without aligning itself with the parties of power, while at the same time avoiding a rupture that would destroy all channels of communication with Erdoğan. This stance aims to preserve the party’s political autonomy and strength within the opposition, but it also carries the risk of political isolation.

However, the lack of coordination among opposition forces leads to missed opportunities to maximize their influence. An indicative example is the CHP’s absence from critical parliamentary initiatives, such as a potential delegation to Abdullah Öcalan, which could politically elevate the process and grant it broader institutional legitimacy. In any case, 2026 appears as the most pivotal point for the future of the Kurds and Turkey in the region.

Nikos Moudouros

Assistant Professor, Department of Turkish and Middle Eastern Studies

University of Cyprus

Published in greek by the newspaper Phileleftheros, 28 December 2025